REPORT FROM THE DECOLONISING SEA TURTLE CONSERVATION: WALKING THE TALK WORKSHOP AT THE 42ND INTERNATIONAL SEA TURTLE SYMPOSIUM, PATTAYA, THAILAND

AMANDA ROBBINS1,#, AILEEN LAVELLE2, BRYAN WALLACE3, CONNIE KA-YAN NG4, KARTIK SHANKER5,6, MICHAEL WHITE7, JARINA MOHD JANI8, HECTOR BARRIOS-GARRIDO9,10, MICHELLE MARÍA EARLY CAPISTRÁN11, MANJULA TIWARI12, GEORGE BALAZS13, RUSHAN BIN ABDUL RAHMAN14, ALEXANDER R. GAOS15, ANDREWS AGYEKUMHENE16, LIVIA TOLVE17, ANDRÉS RAMOS-BENITO18, KELLY STEWART19 & KELLY HOGAN20

1Zoology Department, Nelson Mandela University, Gqeberha, Eastern Cape, South Africa

2 Department of Biology and Archie Carr Center for Sea Turtle Research, University of Florida, Gainesville FL, USA

3Ecolibrium, Inc., Boulder CO, USA

4Department of Chemistry and State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution, City University of Hong Kong, Kowloon Tong, People’s Republic of China

5Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore, India

6Dakshin Foundation, Sahakar Nagar, Bengaluru, India

7Independent Researcher, Glastonbury, Somerset, United Kingdom

8Biodiversity Conservation and Management Program, Faculty of Science and Environment, Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala-Nerus, Terengganu, Malaysia

9Grupo de Trabajo en Tortugas Marinas del Golfo de Venezuela, Maracaibo, Venezuela

10Beacon Development, KAUST National Transformation Institute, Innovation Cluster, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

11Oceans Department, Stanford University, Pacific Grove CA, USA

12Ocean Ecology Network, San Diego CA, USA

13Golden Honu Services of Oceania, Honolulu HI, USA

14College of Science and Engineering, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia

15Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Honolulu HI, USA

16Department of Marine Fisheries Science, University of Ghana, Legon-Accra, Accra, Ghana

17Dipartimento di Biologia, Università degli Studi di Firenze, Florence, Italy

18University Institute for Agro-food and Agro-environmental Research and Innovation (CIAGRO), Ecology Area, Miguel Hernández University, Orihuela, Spain

19The Ocean Foundation, Washington DC, USA

20Wild Earth Allies, Chevy Chase MA, USA

#amandaelainerobbins@gmail.com

Download article as PDF

Disclaimer In this workshop report, we use the terms “Global North” and “Global South” to discuss issues related to global inequality in sea turtle research and conservation. We have chosen these terms for specific reasons:

Avoiding Economic Labels We avoid terms like “high income,” “low income,” and “developed” or “undeveloped,” as these terms often overlook the historical and structural reasons behind countries’ current status, including the impact of colonialism.

Understanding Privilege We recognize that “privilege” can have different interpretations, and there is still debate on its usage within our group – some argue that privilege is conferred by colonial powers while others see it as a result of colonial history where countries that have managed to rise from less privileged circumstances have done so despite systemic challenges. The term “more privileged” in this context denotes countries that have historically benefited from global systems and structures, often at the expense of others. The term “less privileged” is used for countries that have faced challenges due to these same systems.

Global North and Global South Usage The term ‘Global North’ refers to the countries in the Northern Hemisphere, most of which participated in the colonisation of countries in the ‘Global South,’ which refers to countries in the Southern Hemisphere, many of which have been colonised (Patrick & Huggins, 2023). There continues to be global debate about these terms as they originated in the 1970s and are not a consistent geographic reflection of colonisation (Patrick & Huggins, 2023). However, they are used in this context for their simplicity in reflecting colonisation and their recognition as widely used terms.

We acknowledge that these terms may not adequately capture the complexities of global inequalities but use them to frame the discussion in a way that emphasizes historical context and systemic issues.

On 24th March 2024, the first International Sea Turtle Society Symposium (hereafter Symposium) workshop on the decolonisation of conservation was held at the 42nd International Sea Turtle Society Symposium (ISTS Symposium42) in Pattaya, Thailand. This session discussed two recent SWOT Report articles identifying how we participate in colonial conservation and parachute science as individuals and as a sea turtle society (Shanker et al., 2022, 2023). In doing so, workshop participants took time to identify their roles, express their observations, experiences, perspectives, concerns, confusions, and frustrations, and brainstorm ideas of how they would like to see the International Sea Turtle Society (hereafter Society) address these issues. What follows is an account of this meeting, including recommendations for actions that could be taken to begin addressing some of the issues raised.

What Does the Colonisation of Sea Turtle Conservation Refer To?

Within the history of sea turtle conservation, most of our own work and that of the experts we idealize reflect a theme of colonialism in which primarily English-speaking researchers from the Global North travel to remote areas in the Global South to tell local communities how to live and manage/interact with their natural resources (Rudd et al., 2021). These efforts to “educate and train” local populations, though often well-intentioned with respect to ecological goals, frequently overlook the local sociocultural values and economic needs (Brockington et al., 2006; Campbell, 2007; Armitage et al., 2020; Bennett et al., 2021). Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, the sea turtle community is no exception, as we find sea turtle people following the same global migration routes and methods forged by centuries of colonialism (Shanker et al., 2023) in this case, to exploit intangible resources such as knowledge and culture. Importantly, this form of colonisation is not limited to foreign scientists in local communities but also within local communities of different regions.

Often, researchers and conservationists from the Global South are not well-connected to the network of counterparts around the globe and are, therefore, overlooked and undervalued. Possibly, this is due to language barriers, with English being the predominant language used for scientific publication, communication, and collaboration (Dahdouh-Guebas et al., 2003). However, this also stems from glorifying the prestige of the Global North and the Western-centric convention of how research and conservation ‘should be done.’ As such, conservationists of any background should be more aware of the difference between sharing versus imposing their ecological and social ideologies on local and indigenous cultures and be careful not to heroise researchers from the Global North or their methods to avoid further colonisation within regions.

How Has the International Sea Turtle Society Colonised Sea Turtle Conservation?

The Society has been a registered non-profit organization since 1996. Its roots are regional sea turtle conferences held under various names since 1981, aimed at bringing together volunteers and researchers from the southeast of the United States. Therefore, meetings were held predominantly in the southeast United States of America until 1998 (the 18th International Sea Turtle Symposium) when the scope of meetings expanded from regional workshops to international conferences (Figure 1a; International Sea Turtle Society, 2024a). Since then, the Society has come a long way, from a few local attendees to now welcoming a diverse range of participants, including researchers, conservationists, and students. In fact, the virtual format of ISTS Symposium40 in 2022, necessitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, boasted one of the widest geographic range of attendees, attracting individuals from over eighty countries (Pendoley, 2022). In doing so this Symposium also highlighted ongoing issues related to global representation.

Figure 1. International sea turtle symposia (1981-present) by a) global region and b) host nation (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024a). The Global North category is Europe (apart from Türkiye), North America, Japan, and Australia (UN Trade and Development, 2023). The Global South category is Türkiye, South Africa, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Malaysia, Peru, Thailand, and Mexico (UN Trade and Development, 2023; UNESCO Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World, 2024).

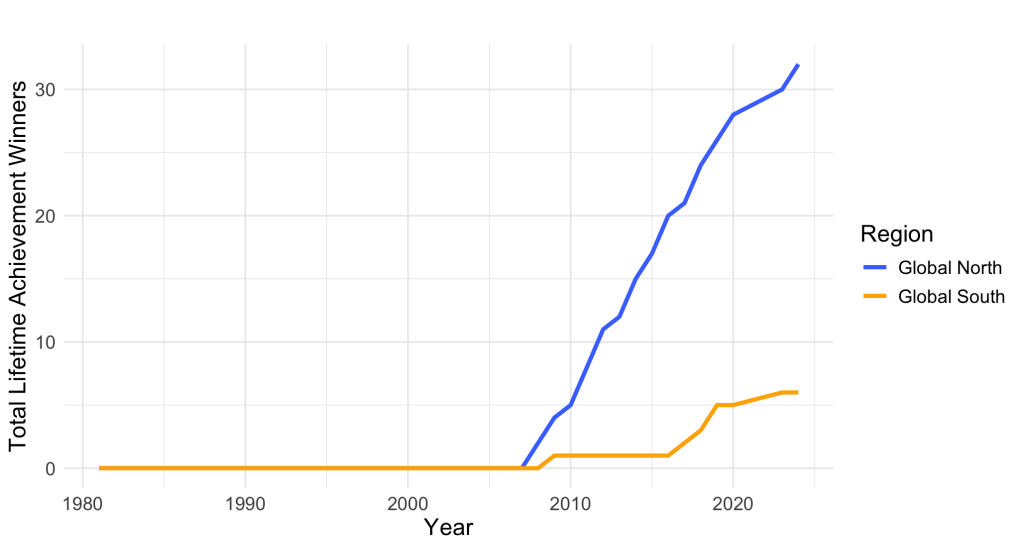

Though the Society was created officially in its current nonprofit status in 1996, its history shows a predominance of Symposia host nations and honourees from the Global North, with growing participation from the Global South in recent decades (Figure 1; International Sea Turtle Society, 2024a). The imbalance is further evident in participants’ geographic and professional backgrounds, the distribution of awards (e.g., the Lifetime Achievement Award has been awarded to someone from the Global North 84% (n=38) of the time), and the locations of symposia events, which have frequently favoured individuals from and countries in the Global North (14 symposia or 58% (n=24) since 1998; cumulatively 31 symposia or 73% (n=42)) (Figure 2; Shanker et al., 2023; Past Proceedings – International Sea Turtle Society 2024). In fact, the only award of which all recipients have been from the Global South is the Grassroots Awards (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024b).

Figure 2. Cumulative ISTS Lifetime Achievement Award winners by global region (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024b). The Global North category is Europe (apart from Türkiye), North America, Japan, and Australia (UN Trade and Development, 2023). The Global South category is Türkiye, South Africa, Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Malaysia, Peru, Thailand, and Mexico (UN Trade and Development, 2023; UNESCO Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World, 2024).

Another important indicator of global differences is the ISTS Student Awards, which have been given for the best talks and posters since 1990. Student Awards are a highlight of the event with many students vying for this distinction and a dozen or more judges giving considerable time to evaluating the presentations and posters. Without a doubt, this plays a great role in incentivizing and inspiring the next generation of sea turtle biologists and conservationists. However, as a result of epistemic differences in what is considered ‘good science’ and likely asymmetries in regional representation, material resources, and training available, a vast majority of these awards have also gone to students from North America 89.8% (mainly the United States). Only 10.2% (21 of 205) of student winners were from an institution in the Global South (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024b).

We suggest these disparities are indicative of the larger issue of unequal access and influence within the field of sea turtle conservation, often described as a form of “colonization” and there is a pressing need for the Society to ensure a more equitable global representation in future symposia.

How Does the International Sea Turtle Society Decolonise Sea Turtle Conservation?

As a collective sea turtle society, we should learn from the mistakes of the past to move forward, as ultimately, the responsibility of reforming how we collaborate and communicate conservation should be equally shared by all identities in the Global North and Global South (Dahdouh-Guebas et al., 2003).

We outline a few ways in how this can be achieved through:

Recognizing that local communities are the guardians of their ecosystems.

Listening respectfully to local community members about their ancestral knowledge and cultural practices within the ecosystems we seek to conserve. As Western-trained researchers, we can learn more from communities besides gathering data for statistical analysis.

Recognising non-English speaking researchers/conservationists and ensuring their work is shared in global forums.

Adapting and integrating commonly accepted scientific techniques to be compatible with local cultural practices.

Recognising that all forms of use, including consumption, deserve meaningful consideration and that sustainable management decisions can be guided through a collaborative integration of Indigenous community knowledge and scientific research.

What Has the International Sea Turtle Society Done So Far to Encourage Decolonisation?

In 1998, the Symposium was hosted at its first international location in Mazatlán, Mexico. Since 2003, the Symposium has been regularly hosted at international locations including Global South venues (Figure 1; International Sea Turtle Society, 2024a). Therefore, of 24 symposia since 1998, 14 have been hosted in Global North countries – 10 of which occurred in the southeast United States – and 10 have been hosted in Global South countries.

The ISTS travel grants started around 1985 through the vision of Karen Eckert, Scott Eckert, and Tony Tucker, with support from Jim Richardson, to increase the participation of students and individuals who are from an underrepresented region and face financial barriers. This long-standing grant is a shining example of prioritising diverse background within our community.

The Symposium Grassroots Award was created in 2011 to recognise participation and contributions by Indigenous and local community members (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024b).

In 2021, Symposia began awarding the Community Grant, which helps ‘build[] capacity for local leadership and community-based conservation[].’ (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024c). The majority (89%; n = 9) of these grants have gone to Global South communities (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024c).

Early in ISTS history, the nominating committee proposed new members of the Board of Directors, and then the general membership voted on these proposed individuals. Attempts have been made to diversify the Board of Directors since the early 1990s. In 2006, direct voting for the Board of Directors was established. While this process has clear advantages, there are limitations as only Society members – i.e., those who can afford to purchase and renew annual memberships – can run for these positions and vote for candidates. As such there is an inherent structural barrier in Board of Directors membership and representation that needs to be addressed (Shanker, pers. obs.).

What More Can the International Sea Turtle Society Do?

Although the Society cannot decide how its members conduct their work or if Symposium attendees should decolonise sea turtle conservation in their region, it can contribute to the cause by setting examples and creating new norms. Therefore, during the Decolonisation Workshop of ISTS Symposium42, participants discussed concrete steps that could be taken to make the Symposium – and thus the Society – more inclusive and less ‘colonial’ in form and function. Some practices that the Society can adopt include:

Implement satellite meetings

Apart from the issue of the Symposium’s carbon footprint, our opportunity to truly learn from and network with one another is minimized if research and persons from the Global South or students and early career researchers – who are often on the frontlines of novel science – continue to be underrepresented. One potential way to address this systemic inequity could be to host regional satellite meetings in conjunction with the Symposium. Regional satellite meetings would create an opportunity for collaboration with neighbouring researchers and conservationists while still contributing remotely to the annual symposium. These satellite meetings can be further accommodated for time zone differences by saving and sharing recorded presentations with global participants via a symposium archive.

Improve access and collaboration

As our society grows, so do our sessions, and even those who can afford to attend Symposium annually cannot participate in each session and workshop. Pre-recording and archiving talks, meetings, discussions, workshops, and digitised posters would allow broader, more equitable access to the symposium’s educational wealth. Archived sessions would allow for access to content after the symposium has ended, accessible to a larger audience, including future researchers, conservationists, and students not yet in the sea turtle world.

The use of remote technology would have the additional benefit of facilitating more time and space for workshops, discussions, and networking. By inverting the current time and space allotted between the oral sessions and workshops, the ISTS program will allow for more opportunities to interact and collaborate with new and former colleagues.

Source translators

Presenting an oral, poster, or even a discussion point during a workshop can be intimidating; doing so in a different language amplifies the sentiment. Language barriers could be a deterrent for some researchers as they may not have the speaking or writing skills in English to share their work. They are, therefore, presenting their work under strained capacity and they may be unable to garner the attention their work deserves. Including translators via multilingual volunteers or even allocating funds for translators allows for more work to be displayed and shared, more conversations and collaborations among attendees to take place, and nurture recognition of their work.

Additionally, including a written translation service that allows participants to write, translate, and submit questions during live sessions, which moderators can read on their behalf.

Ensure a diverse board of directors

The Board of Directors that helps guide, manage, and represent the Society should be a reflection of its members. Having minimum regional representation within the Board of Directors, promotes diversity within an already existing international society, encourages inclusion and collaboration by leading as an example, allows for a more immediate recognition of global perspectives; and further identifies and celebrates counterparts from regions or backgrounds that may have been overlooked in previous years.

Elevate and celebrate diverse conservation practices

As sea turtles occur globally, so do the conservation efforts to protect them and their habitats. As a society working to conserve these animals and their ecosystems, we have the unique privilege of being privy to various communities and cultures. However, as this workshop group has noted, we often promote uniform conservation practices, usually within the realm of Western-approved strategies. As we enlighten ourselves about the colonialism of this mentality and how to decolonise our practices, we should investigate, share, and celebrate the varied sea turtle conservation practices occurring at global nesting shores and within international coastal communities. In doing so, we provide ourselves with an opportunity to learn from one another, inviting new methods and strategies that have the potential to increase the success of conservation interventions.

We suggest formally celebrating these diverse conservation practices and successes as:

a. part of our annual Decolonising Conservation workshop; and/or

b. a discussion point within relevant annual meetings and/or ISTS Board meetings.

Alongside celebrating diverse conservation practices, we recognise a need to promote the Symposium Grassroots Award further, which is an initial effort to recognise the efforts and successes of Indigenous and local communities.

Create an equity committee

To enact the above suggestions and proactively propose further accommodations, the society could establish an Equity Committee to support the ISTS, particularly the President and their organizing team. The Equity Committee could:

support the Society Board of Directors and Symposia organisers with the aforementioned suggestions, e.g.,

implementing satellite meetings,

instilling remote technology, and

providing and managing translation services.

perform an audit of the Society and Symposium to identify opportunities to implement further inclusivity measures (e.g., review membership and Terms of Reference for the Symposium Program Committee, Student Award Committee, Travel Grant Committee, etc.);

organise an annual Symposium meeting or workshop focused on topics of equity, inclusivity, and decolonizing sea turtle conservation; and

assist with improving social media accounts, ensuring posts are frequent, informative, inclusive, and relatable.

This committee would raise awareness, suggest improvements, and address inequalities including those outside of decolonisation, like providing childcare for symposium attendees.

Moving Forward

The decolonisation of conservation is a necessary movement being discussed globally (Dahdouh-Guebas et al., 2003; Rudd et al., 2021; Tan, 2021). By adopting the above suggested practices within sea turtle conservation, the Society has an opportunity to help facilitate the forward movement and spread of decolonising conservation. Doing so will set an example, not only for our society of sea turtle conservationists, researchers, students, and enthusiasts, but for other conservation societies as well. Furthermore, participating in the decolonization of conservation aligns with our International Sea Turtle Society mission statement, “to promote understanding, appreciation, and value of sea turtles and their habitats through the exchange and sharing of information, techniques, ideas, and inspiration that will promote actions from local to global levels, for the advancement of sea turtle biology and conservation” (International Sea Turtle Society, 2024d).

Literature cited:

Armitage, D., P. Mbatha, E. Muhl, W. Rice & M. Sowman. 2020. Governance principles for community-centered conservation in the post-2020 global diversity framework. Conservation Science and Practice 2: e160. DOI: 10.1111/csp2.160.

Bennett, N.J., L. Katz, W. Yadao-Evans, G.N. Ahmadia, S. Atkinson, N.C. Ban, N.M. Dawson et al. 2021. Advancing social equity in and through marine conservation. Social Equity in Marine Conservation 8: 711538. DOI: 10.3389/mars.2021.711538.

Brockington, D., J. Igoe & K. Schmidt-Soltau. 2006. Conservation, human rights, and poverty reduction. Conservation Biology 20: 250-252.

Campbell, L.M. 2007. Local conservation practice and global discourse: A political ecology of sea turtle conservation. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 97: 313-334.

Dahdouh-Guebas, F., J. Ahimbisibwe, R. Van Moll & N. Koedam. 2003. Neo-colonial science by the most industrialised upon the least developed countries in peer-reviewed publishing. Scientometrics 56: 329-343.

International Sea Turtle Society. 2024a. Past Proceedings. https://www.internationalseaturtlesociety.org/publications/proceedings/. Accessed on July 24, 2024.

International Sea Turtle Society. 2024b. Past Award Recipients. https://www.internationalseaturtlesociety.org/awards/past-award-recipients/. Accessed on July 24, 2024.

International Sea Turtle Society. 2024c. Community Grant Program. https://www.internationalseaturtlesociety.org/awards/community-grant-program/. Accessed on July 24, 2024.

International Sea Turtle Society. 2024d. Who Are We? https://www.internationalseaturtlesociety.org/about-us/the-ists/. Accessed on July 24, 2024.

Patrick, S. & A. Huggins. 2023. The term “Global South” is surging. It should be retired. Carnegie Endowment https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2023/08/the-term-global-south-is-surging-it-should-be-retired?lang=en. Accessed on July 24, 2024.

Pendoley, K. 2022. President’s Report for the 40th Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation, Perth-Online, Australia, 25-28 March, 2022. Indian Ocean Turtle Newsletter 36: 32-34.

Rudd, L.F., S. Allred, J.G. Bright Ross, D. Hare, M. Nomusa Nkomo, K. Shanker, T. Allen et al. 2021. Overcoming racism in the twin spheres of conservation science and practice. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 288: 20211871. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2021.1871.

Shanker, K., M.M. Early Capistrán, J. Urteaga, J,M. Jani & B.P. Wallace. 2022. Moving beyond parachute science in the sea turtle community. SWOT: State of the World’s Turtles 17: 36-37.

Shanker, K., M.M. Early Capistrán, J. Urteaga, J.M. Jani, H. Barrios-Garrido & B.P. Wallace. 2023. Decolonizing sea turtle conservation. SWOT: State of the World’s Sea Turtles 18: 31-35.

Tan, K. 2021. Just conservation: The question of justice in global conservation. Philosophy Compass 16: 1-12.

United Nations (UN) Trade and Development. 2023. Classifications – United Nations Trade and Development (UNCTAD) Handbook of Statistics 2023. https://hbs.unctad.org/classifications/. Accessed on July 24, 2024.

United Nations Education, Science, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Organization for Women in Science for the Developing World (OWSD). 2024. Countries in the Global South (by region). https://owsd.net/sites/default/files/OWSD%20138%20Countries%20-%20Global%20South.pdf. Accessed on July 24, 2024.